When All Else Fails: Broken Cables, Lost Hooks, and Options

Though the mission had started out easy enough, three hours later it was the single worst moment of my life and by far my worst day in a helicopter. We were 240 miles offshore. It was pitch black, freezing cold, my best friend, Mike, was in the water and the hoist cable was – strand-by-strand – coming apart in my hand. It was ruined, the hoist was completely jammed, and we didn’t have enough fuel to make it to shore. We were going to crash after the engines flamed out and Mike was going to freeze to death soon after. We were all going to die and we all knew it.

I’m writing this now, so we were obviously wrong. But we got lucky. The wind switched from a headwind to a tailwind and allowed us to make it to the beach with the gauges bouncing off empty. Mike wasn’t lost because our C-130 crews shut down two engines to stay on scene until a second helo could pick him up, five and half hours later, unconscious and close to dead – just not.

Every mission I’ve been on adds up to my experience and how I think, but that particular mission is where I learned something important. There have been other missions and other problems since then, but that was the one where I learned this inescapable truth: sometimes your plans fall apart. Things will go wrong. It will probably be something you didn’t think about.

Being lucky is not a reliable backup.

You are Hanging from The Weak Link

A brand new hoist cable on a helicopter in perfect condition will start coming apart at between 3,500 and 3,900 pounds of load. The helicopter (usually) is stronger, the basket or litter is usually stronger, even the swage that holds the hook on the end of the cable is stronger. The maximum force your hoist cable can withstand under a static load before internal damage occurs is just 1,980 pounds. When you consider the shock loading (if two persons on the hook fall through two feet of cable slack, it’s an easy 5,000 pound shock load), small knocks and rubs on vessels, rocks, and deck railing, and the constant immersion in salt water, your hoist cable easily becomes a fragile thing indeed.

(Note: The overload clutch will mitigate, not eliminate, the possibility of cable failure. We know this because every modern failure of a hoist cable occurred on a hoist with an overload clutch.)

So let’s clear this up. You can ruin a hoist cable and your hook can be lost. And though I don’t have the data on how many times this has happened or what caused it, I do know this was true every time a cable failed on a helicopter: the crew did not take off thinking it would happen.

If you are lucky, you’ve got a second hoist – a completely separate hoist system to cover whatever may go wrong with your primary. Most helicopters don’t. Break a cable – or just damage one – and your only hope at finishing the mission or getting your friends back is a quick splice – a secondary hook attached to a splice plate or other temporary device to help you turn nothing (a broken cable) into something – a shorter hoist cable with a hook on it. The damaged or broken strands of the cable are cut off cleanly, a temporary replacement hook is attached, and hoisting may continue. It’s not a perfect solution (a second hoist system is) but for most of us these simple devices are all that make the difference between just a bad day and a tragic one.

If you ever find yourself with a shredded cable in your hands during a mission, you want your quick splice to be two things:

- It should be stronger than the cable. A mission that stressed your gear to the point of breaking is not the time to introduce a new weak link into the system. Your quick splice should connect the new hook to the old cable in such a way that you can count on it for at least the rest of the mission.

- It should be easy to use. You may not believe this, but if you do find yourself holding a shredded cable during a mission, you’re going to be stressed. Easier is better. No way to do it wrong is best.

Options

There are three widely available options for hoist quick splices.

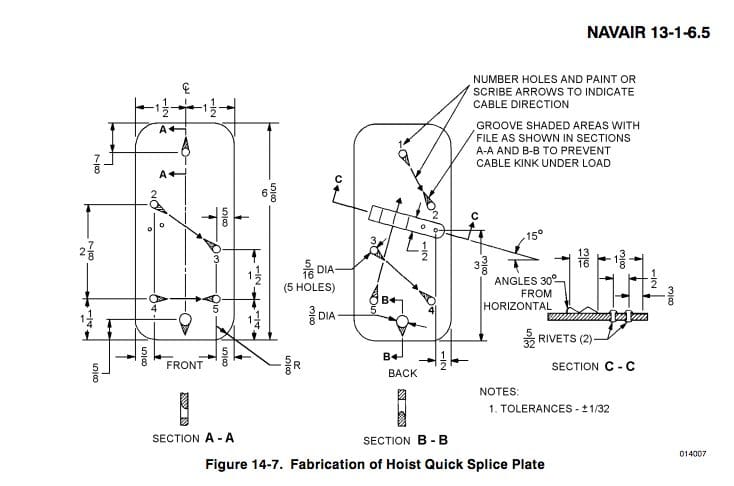

Manufacture in accordance with the U.S. Navy

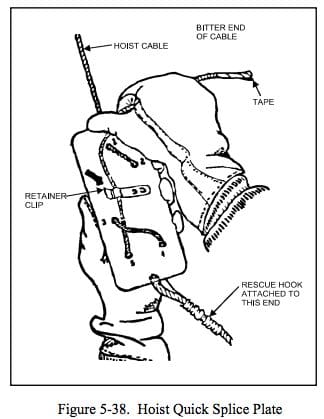

The U.S. Navy actually manufactures its own helicopter cable splice plate. The gang in the metal shop take an aluminum plate, drill holes in it, add a clip and some hardware, attach a hoist hook and keep it on the aircraft. The NAVAIR 13-1-6.5 has detailed plans (expand image below) for how to make one. Consisting of five holes through which the bitter end of the hoist cable is laced, the plate relies on the tension created in the turns of the cable to hold the plate in place. Rigged properly, they will hold the hook and exceed the load limit of the hoist – but it may not be as strong as the original cable. The SAR Manual adds an important warning:

“Failure to rig the cable through the hoist quick splice plate properly will result in the cable slipping out of the quick splice when tension is applied. ”

We can break that down to “using it wrong is bad,” and that is true of everything I suppose, but still there seems to be a complexity to this otherwise simple device, and confidence in its ability to hold a load comes after you put it under a load.

An Improved Commercial Version of the Splice Plate

A company in Virginia created an improved version of the Navy’s splice plate with some features that made it easier to use and perhaps more secure and also added a topping plate to engage the hoist limit switch. Like the Navy device it is a metal plate with a series of slots (versus holes to be laced) for the operator to use in wrapping the broken cable around the plate itself. When placed under a load, the turns of the cable create the tension that hold the plate and thereby the attached new hook to the cable.

With practice, rigging this splice is easier than the Navy version but there are ways to use the device incorrectly that may work. The manufacturer recommends a maximum load of 600 pounds, which is the typical limit of a hoist in any case, but this is also injecting a new weak link into the system.

A Different – but Older – Idea

Realizing there was an issue with the effective use and load capability of the splice plates that were available, LSC founder Sam Maness applied an old solution to attaching a cable to a load: mechanical compression. Using a simple wedge block design, the LSC quick splice applies external compression to hold the cable to the plate. The heavier the load, the more secure the cable becomes, making slipping or separation from the plate impossible.

With only one way to rig the device, “using it wrong” is also impossible. Simple is better and stronger is better and instead of a wrapping process, hoist operators have just two steps – thread and tighten – to create a near-permanent and instantly reliable connection between the replacement hook and the old cable.

A quick splice would not have made any difference to my friends and me years ago when our hoist cable failed. But we learned the hard way that helicopter hoists are complex systems and complex systems can break. If the weakest link in that system fails, having an easy-to-use and reliable backup is possible. Choose wisely, train often, and stay safe out there.

Watch this 5 minutes video on LSC Quick Splice:

A demo on the use and load capability of the LSC Quick Splice to accompany this article: http://wp.me/p6YJti-3dH

Hey Mario, USN Rescue swimmer and PR! Brought MC Farmer through SAR School (85). Thing is… the weakest link and Time! We taught “double rescue hook” and limits (testable). NOT… other limits (stantions etc…). This new outlook still requires time, ie.. cutting/looping! Not good. Cont me.

The best option is a second hoist system. Too few have that option. If you can replace the hook in 3 minutes, my guess is you’ll make it out of there before bingo, yes?